Review: WHAT YOU GONNA DO WHEN THE WORLD'S ON FIRE?

The Gulf South is awfully bleak, you know. Is there room for anything else?

While many members of the Gulf South black community are featured in What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?, from single mothers to small business owners and Mardi Gras Indians, the most outspoken would be The New Black Panthers for Self-Defense organization. Director Roberto Minervini’s film is surprisingly given front row access to this pretty aggressive group - not to suggest that they don’t have every reason to be aggressive. He captures everything from induction meetings, genuine community outreach, armed door to door investigations, and protesting in the face of police brutality - which does go down. They’re righteous but… kinda terrifying too. And it was only afterward that I looked them up on the Southern Poverty Law Center’s website, where I unfortunately confirmed some not so great suspicions about their mission statement.

World’s on Fire? isn’t at all about agreeing or disagreeing with anyone. In fact, the camera crew maintains a strong “fly on the wall” type angle towards who and what is being documented. It comes strikingly close to tipping its own scale and flat-out endorsing solidarity with the extremists, but is able to achieve a balancing act that works for the best. For the most part, I was nodding my head with those shouting “black power!”, but when the word “zionist” came up, and when a citizen’s inquiry into a neighborhood murder involves live machine guns meant to intimidate, I grew curious as to Minervini’s thesis.

In the times of Trump, white supremacy has been both indirectly and most directly encouraged, running rampant across the country in dangerous and ever-increasing numbers. This is a world on fire most assuredly. And how does a class and race of people act and live in such a burning environment? We see, through a few side stories in 2017, set mostly in the New Orleans region, the harsh realities that are reconciled with and heartbreakingly understood, not to mention the lengths individuals and masses go to just to survive, thrive, and grasp onto some form of justice. The New Black Panthers are but a small portion of the story, but the piece they inhabit represents a potential future for my two favorite characters.

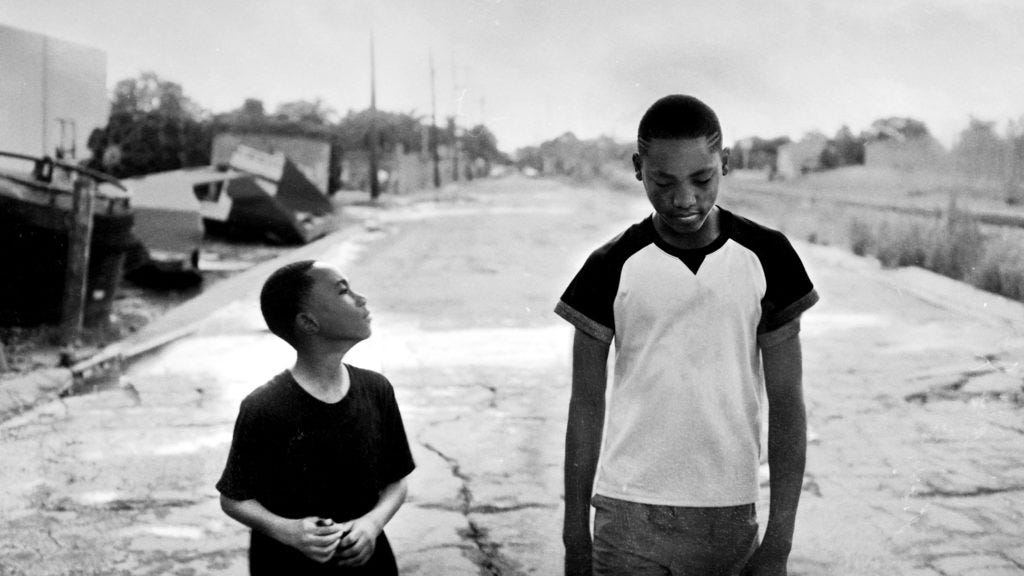

There’s a child and a bar owner, followed separately, who caught my attention in a way most resonant. The child, an older brother, does his best to avoid trouble in and around his home, while obeying the words of his mother. However, the dangling carrot-like curse of his formerly incarcerated father looms overhead, as troubles in school crop about. It’s clear that his younger brother looks up to him, but what isn’t is just how the older one is able to handle such great and influential responsibility. When he says “kids your age don’t shoot,” it’s a devastating but honest observation. The sheer weight of this world lays heavy on his shoulders.

The woman, who runs a bar on the brink of closing, does her best to keep her family and friends close and out of the cold embrace of a region that’s indifferent to them at best, and awfully violent to them at worst. Almost everyone she meets gets a personal story from her, some philosophical and inspiring anecdote on life and morality that always rings true and always comes from a genuine heart. She too wears stress, but in her case it all comes out through teardrops, cracks in her voice, and awkward smiles during painful recollections. Normally, she’s pretty stoic, but it’s in these climactic moments that her vulnerability shows strength in overcoming the tragic.

World’s on Fire isn’t as lyrical or as well-composed as Hale County This Morning, This Evening - the vastly superior documentary narrative hybrid - in fact, I was wishing for more of an editorial voice in this picture, but despite needing some trims in the runtime, the film accomplishes a story more interesting than others of the genre. Perhaps in being too plain, Minervini and crew stripped themselves of power and gave it back to the subjects. Or maybe they were flexing a vision of sorts, one that mimics naturalism within documentation, by way of just floating in and out of conversation and revelation.

On this, I’m confounded.

The New Black Panthers of Self-Defense are indeed troubling, especially in what Minervini chooses and doesn’t choose to show us, from the glimpses of machine guns to that utterance of a Jewish slur, assuredly forcing reactions and connections from the audience. Proper context would’ve been nice, but honestly, we already know the condition of these things as of late. Just look out your window. What do you see? People trying to get by, but being put down in one form or another. Down the block might be their past, up the street their future. What will determine the direction they go?

This film doesn’t know nor does it choose to. What does World’s on Fire go for instead? A convenience in being a spectator and anxiety in observation. It’s afraid. We’re afraid, too. The subjects? No time to be.

RATING: 3 / 5